Indigenous History with Thanksgiving

November 21, 2022

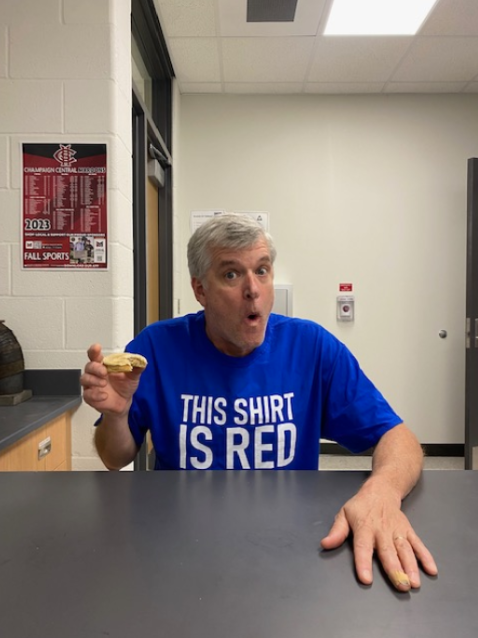

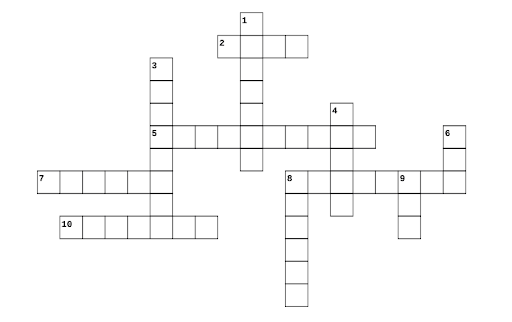

This is a piece of artwork showcasing what is widely regarded as the first Thanksgiving. However, it tells far from the whole story. (Image found here)It is often taught that the holiday of Thanksgiving is a joyous, happy occasion. In elementary schools across the country, as November falls, stories of friendship and happy meals shared are passed around from teacher to student. In reality, what went on during the founding of the holiday is vastly different than what has been recounted.

To understand the event that took place, some background information is required. There are two groups that will be discussed in this article: the Wampanoag people and the pilgrims of Plymouth.

The Wampanoag people are of a Native American tribe that had existed for thousands of years before what has been considered the first Thanksgiving. They had dominated what is now the south-east portion of Massachusetts. Between 1616 and 1619, disease was brought to the tribe by European sailors who had been visiting for decades prior. The exact disease is unknown, though theories have varied from smallpox to leptospirosis. During this time, around 90% of the Wampanoag population died due to the illness in what has been referred to as “The Great Dying”.

The Pilgrims had come from England on the Mayflower. This group of people were of differing religious beliefs, and had wanted to practice these freely in this newly discovered world. So, in the September of 1620, all 102 of them made their way onto the boat the Mayflower, and set sail to North America. The trip was arduous, and lasted nearly two and a half months.

At last, they reached New England, and began to build their new village. Many of the pilgrims stayed on the Mayflower during the first winter, yet that did little to protect them from the harsh realities of their new climate. By the end of the season, more than half of the original settlers of the Mayflower had died

In March of 1621, the pilgrims were approached by two Native American leaders. One of these leaders would be known by history as Squanto. He had been sold into slavery in London in 1614, before escaping and learning English. Squanto returned to North America in 1619, when he found villages of Wampanoag people dead due to the spreading illness.

Due to the weakening of the tribe, the Wampanoag leaders realized they had to make alliances in order to survive against rival ones. So, as a last resort, they sought to ally themselves with the Plymouth Pilgrims. They taught them their trades, and educated them in practices such as growing corn and catching fish.

That November marked the Pilgrims’ first successful harvest. The governor of Plymouth, William Bradford, extended an invitation to the Wampanoag people. Around 90 showed up to the feast, greatly outnumbering the estimated 50 surviving Pilgrims. It is thought that the Wampanoag people even contributed a great deal of food.

The feast was splendid. Fowls were caught and cooked. The people all socialized and drank together. Though relations were strained, they basked in this achievement together. It was here that a treaty was made between the two groups, one that was a promise of peace.

So that is where the story ends. The Wampanoag helped the Pilgrims survive, and in return, a feast was thrown. Everyone was friends. They all lived happily ever after. Right?

Well, not quite.

After the feast, the Pilgrims kept encroaching on more and more of the Wampanoag’s land. And as the Europeans saw more and more of Plymouth’s success, more and more made the voyage across the Atlantic. Relations between the residents of Plymouth and the Wampanoag became increasingly strained. Until one day, they cracked.

In 1636, fifteen years after the first Thanksgiving, it was accused that the Pequot people had killed one of the settlers. It escalated and snowballed until, in May of 1637, the settlers went to one of the Pequot villages, specifically Mystic Fort. They set the fort on fire, and killed whoever they found inside. It is estimated that 500-700 people were killed that day.

This event ended up being a turning point in the Pequot War, which was being fought at the time. Though the Native American tribes tried to retaliate once more, the damage had already been done. The treaty between the citizens of Plymouth and the Wampanoag lasted until King Philip’s War in 1675. This, unfortunately, was not the last time lives were taken because of tensions with Native Americans.

After what became known as the Mystic Massacre, it was declared by the governor of Plymouth that for the next hundred years, Thanksgiving would be celebrated on that day to commemorate the event.

It wasn’t until Lincoln was president in 1863 when Thanksgiving was declared a national holiday to help rekindle the bonds between the states, and when it gained the meaning that it has today.

And there it is, the history of Thanksgiving. It’s important to remember the true backstory behind these seemingly innocent events and holidays. There is often another side of the story, another face to the coin. It shouldn’t be buried; it should be challenged.

Sources:

- The Real History of Thanksgiving Is Darker Than You Learned in School (insider.com)

- Thanksgiving 2022 – Tradition, Origins & Meaning – HISTORY

- Thanksgiving Day | Meaning, History, & Facts | Britannica

- Opinion | The Horrible History of Thanksgiving – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

- Celebrate Indigenous History This Thanksgiving | Sierra Club

- Recognizing Native American Perspectives: Thanksgiving and the National Day of Mourning | National Geographic Society

- The History of Thanksgiving from the Native American Perspective (nativehope.org)

- The Tragic Truth Behind Wampanoag, Squanto, & the Thanksgiving Story | Smithsonian Channel

Karina Josephitis • Nov 22, 2022 at 11:04 am

this is such a good article and this stuff is so important for people to know. great job!!

Kaitlyn Shoemaker • Nov 22, 2022 at 10:57 am

I like how descriptive your article was! It was very informational and overall very well written. Great job!